TONY MILLER’S FAMILY STORY.

By Mary-Ann Inglis (nee Miller)

From the recollections of my aunt Angela Mouzouris and father, Tony Miller

FOREWORD

My grandparents, Constantine and Marianthe Malliaroudakis (Miller) came from an area of Turkey, once known as Asia Minor. The population of this area was mainly Greek Orthodox in the period prior to Seljuk and Ottoman Turkish Rule. In 1453, the city of Constantinople fell to the Turks, and this City or Polis, so sacred to the Greeks was renamed Istanbul. This marked the end of the Byzantine Empire, a multi ethnic state ruled by the Greeks and the centre of the Greek Orthodox Church. As a consequence, the Greeks citizens of Asia Minor were forced to live under Turkish rule as citizens of the Ottoman Empire. In 1832, a Greek nation state was formed consisting of the Peloponnesus and a few islands. Over the next 115 years, Greece gradually extended its territories to its present borders with the addition of the Dodecanese in 1947. Many surrounding areas, which had been inhabited by Greeks for millennia, were still not included in this territory and the most significant of these were Cyprus and Asia Minor. The Greeks yearned to redeem their City and reclaim the millions of Greeks who still lived within the Ottoman Empire.

During the nineteenth century, the Greeks who lived along the eastern seaboard of Asia Minor had created a prosperous, educated, cultured society, particularly in the areas around the city of Smyrna. It was referred to as the Paris of the Middle East. Many workers came from the poorer areas of Greece proper, to work in Asia Minor and earn money to send back to their families at home.

Around 1914, there was an emerging influence of Turkish pride and nationalism in Anatolia, under the influence of the ‘Young Turks’. Their mission was to rid their land of the Greeks and create a sovereign Turkish state for their own people. There was an outburst of killing and pillaging of the Greek population, and this caused the first Diogmo, or expulsion of the Greeks. When the fighting settled, many Greeks later returned to their homes and businesses to rebuild what had been lost. In 1919, in the aftermath of World War 1, the Greek Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venezelos, directed a Greek military force to land in the zone around Smyrna with the approval of the Great powers (Britain, France, Germany). Their purpose was to protect the Greeks of the region until a referendum was held, to decide the future of the area – to stay Turkish or become Greek. Unfortunately the Greek politicians told the army to proceeded north and reclaim other territories. They dreamed of making Constaninople a Greek city once again. This action was not agreed to by the Great Powers and they withdrew their support for Greece. The Greek soldiers were poorly led, poorly advised and had no idea of the strength and organisation of Turkish forces lead by Mustafa Kemal. By September 1922, the Greek army was routed and fleeing in disarray. The Asia Minor Greeks were left unprotected and they suffered the revenge of the Turks for the excesses of the Greek Army. Civilians were butchered, Greek properties were looted, and the Greek and Armenian quarters of Smyrna were burned to the ground. (Milton 2008). Those who lived along the coast and who had boats were able to escape. Those living inland were trapped. An estimated 3 million Greeks and Armenians were murdered between 1914 and 1922. The small nation of Greece suddenly had to cope with one million brutalized, homeless, sick and hungry refugees who fled to her shores with nothing but the clothes they wore. My grandparents, aunts and father were among them.

TONY MILLER – MY FATHER’S FAMILY STORY

I sit here looking out over the lush green of a Brisbane summer day, and my heart is full of thankfulness. I am thankful for this wonderful country, Australia our home, and the goodhearted spirit of the Aussies, our fellow countrymen, who gave my forbears sanctuary after the tumultuous events of 1922.

The events that led to my grandparents’ journey to Brisbane are history now. They were born in another time, another place, another world. They were brutally catapulted from their prosperous lives in Asia Minor and scattered into destitution to the other side of the globe. Their world had literally ‘turned upside down’.

My Papou’s (grandfather’s) story began after the first Turkish uprising of 1914 which forced him to sail to America to joined his brothers in a chain of grocery stores which sold Greek and American foods. He passed through Ellis Island, New York, and, as was their custom, the clerks processing the immigrants anglicized his name, from Constantine Malliaroudakis, to Gus Miller. Foreign names were not accepted in those days and had to be westernized. Papou lived in Chicago and there he married his first wife, Irene. They had two little girls, Angela and Alexandra. Irene died in the great Influenza Pandemic of 1918, leaving him alone to care for his daughters, now aged three and two years. At the same time, his visa expired and he was forced to return to Asia Minor. As a gambro (eligible bachelor), he was highly sought after. He was, they whispered, ‘O Americanos’, back from the land of opportunity and independently wealthy. A marriage was soon arranged between Papou my grandmother, Marianthe, who herself came from the well established and distinguished Karistinos family.

With the American dollars he had saved, Papou became a merchant in Tsesme, where he owned a warehouse and traded in tobacco, dried fruit, spices and foods. My Aunt Angela describes her father as a gentleman working in his office at the back of the warehouse. “He never got his hands dirty’, she said. Then, as now, those who could earn their living without manual work were accorded a higher status in society than those who performed labouring and farm work.

The port of Tsesme was a prosperous place, renowned for its dried fruits, tobacco, hand woven rugs and emerging oil production. The nearby city of Smyrna was cosmopolitan, cultured and sophisticated. It had schools, universities, hospitals and an Opera House. All the major empires – Britain, France, America, Germany – had established consular services and colleges of education there. The family’s circumstances were very comfortable.

Papou built a two storey home of marble which boasted indoor plumbing. Servants tended to the children – his two daughters, and my father, Tony, who was born in 1921. There were plans to build a holiday home at Loutra. However, life as they knew it was lost irrevocably after September 1922.

It was September 1922 and Yiayia (grandmother) had a brother, Adonis, who was a captain in the Greek army. The Greek army had advanced into Turkish territories, hoping to secure more lands and reclaim Constantinople for the Greeks. However they were soundly defeated and retreated from Mustafa Kemal’s troops in disarray. The Turkish people, both army and civilians took a terrible revenge on the Greek and Armenian populace. Yiayia’s brother was fleeing with his company on horseback when he made a detour to Tsesme to warn his sister and family about the coming annihilation. It was in the dead of night when he and his troops galloped into Papou’s courtyard to wake them. ‘Get out, get out now.” He shouted, “ There’s no time to pack – the Turks are slaughtering everyone’. My father was two years old at the time and has no memories of that night. But Angela was eight and she remembered running into the courtyard, under the horses and around the soldiers as her parents spoke to her uncle assessing their situation. The neighbourhood erupted as people were woken, and ran about crying in terror in the dark. The family home was on a little bay, from where they could see the island of Chios. They now boarded their fishing boat and fled there. Chios was to be their home for the next two years.

Hundreds of thousands of refugees spilled onto the beaches of Chios over the next few months. The island was not equipped to handle the crisis. Most people were housed in old empty warehouses and given basic, starvation rations of flour to live on. Food and medical aid was being assembled in Greece, but it would not arrive for weeks – too late for the refugees, who were already dying of starvation and disease. The American Red Cross was the only relief agency which had people and supplies ready on the ground to keep people alive until the situation stabilized. It was also difficult for the local population of Chios. The price of food soared, as did the black market. The refugees were ill with diseases such as yellow fever, blackwater fever, dysentery, tuberculosis and influenza and this threatened the Chiotes as well. There was no clean water, and sanitary facilities such as latrines were very limited. They were starving, covered in lice and filth, there was not enough food or shelter, and winter was coming. Remember, there were no antibiotics then. Entire families succumbed and died. (de Vries 2000:pp158-178)

Papou, however, had made provisions for such an eventuality. During the first exodus in 1914 many Greeks had remained behind on assurances of protection from their Turkish friends. Afterwards, most had returned to their properties, rebuilt, and started again. Some Greeks thought that things would be the same this time also. They could not believe that their Turkish friends and neighbours would turn on them. But Papou had a premonition that things were going to be worse this second time. He and Yiayia had taken precautions. They had put documents such as the family’s Orthodox wedding and baptismal certificates into a suitcase so that they would be able to establish their identities should they become homeless and stateless. He and Yiayia had also hidden one thousand gold coins (chrises lires) as a precaution against hard times. As things turned out, he had one hour’s notice in the dead of night to get out. But he was ready.

When the family fled, Marianthe’s father, the Karistinos patriarch, along with the elders of other prominent families, decided to remain to try to protect the family’s homes and businesses. He hoped to be able to deal with the Turks to save what he could. This Expulsion, however, was going to be very different to the first one. Months later, Marianthe’s family learned that the Turks had come looking for members of the Karistinos family in particular. Angela said that the family had owned a German shepherd dog, named “Kemal”, and this had outraged the Turks. When the Turks found Marianthe’s father, they arrested him, and with other Greek prisoners, had marched them to the outskirts of Tsesme. There was a tree in front of a kafenio (coffee house), on which the Greeks had painted the Greek flag. These prisoners were ordered to scratch the flag off the bough of the tree with their bare fingernails and then they were all shot and killed. The family had lost everything.

Angela remembers that the family rented a nice house with an orchard in Chios, just outside the capital. She did not remember ever going hungry or suffering the privations that others experienced. Because she and her sister Alexandra had been borne in America, they were American citizens, and as such, the family continued receiving child endowment payments for their support. Papou also earned an income working as a money exchanger. They lived in Chios for two years and their second son, Jack was borne there. Papou tried to return to America, where he could have rejoined his brothers in business, but he was unable to gain the necessary visas. However, they were able to obtain sponsorship to come to Australia, as Yiayia had relatives living in Brisbane.

The family arrived in Brisbane in 1924. Papou, Yiayia, Angela, Alexandra, Dad, his brother Jack, and Papou’s step-mother-in-law, who was called ‘Nene.’ My father was aged five at the time. My grandfather was an unskilled Greek immigrant with a limited vocabulary of English. Jobs were scarce. He was forty nine years old, he had six dependents and his life had been uprooted for the third time. It must have been so difficult for them to start again here. Europeans had barely heard of Australia much less a town called Brisbane in the 1920’s. Their world was the Continent. Their commerce, fashions, foods and culture were influenced by those of Greece, Turkey, France, Italy, Germany, Great Britain and America. Their customs and traditions were those of Greek and European society. The ways of family, social and civic life in Australia were foreign to them. They might just as well have emigrated to the Moon.

They moved into rented premises in George St which was one of Brisbane’s inner city main streets. It was a three storey building, consisting of living quarters upstairs, a shop at street level and a basement downstairs for food preparation. The basement also opened onto a small backyard where they were able to keep chickens. The Great Depression was coming and there were no jobs, so my grandparents opened a business selling fish and chips (hot potato chips), foods which were very popular with Australians.

Selling Greek food was not an option for them. Australia was an Anglo Saxon, Anglo Celtic society and because it was geographically so far from Europe, it was also very insular, unaccustomed to the ways of people from eastern backgrounds. The locals viewed newcomers with suspicion and they certainly would not have bought “foreign food”. Since the locals would not adapt to them, the newcomers adapted to the locals. Dad remembers Papou saying that it would not need much skill to dip fish and chips in batter and cook them in oil and so he improvised as he went along. One day a customer asked for oysters, a food unfamiliar to Papou. So my grandfather dipped the oysters, still in their shells, into the batter, and fried them as if they were fish. The customer was not impressed, but Papou was not deterred and kept trying and learning from his mistakes. He gradually expanded the menu to include other foods that Aussies loved, such as pig’s heads and trotters. Papou had no cooking skills nor was he accustomed to working with his hands, yet he somehow learned how to cook this food which was foreign to him and so different to his more sophisticated Greek cuisine.

Every day, Papou rode to the fish markets on a large tricycle which had baskets on each side for transporting the produce back to the shop. On one of his early trips to the markets, he returned with four kerosene tins filled with mullet roe. Yiayia was furious. ‘What are you doing, buying expensive food like this?’ she exploded. ‘Gyneka mou (Wife)”, Papou replied, “ I didn’t buy it – they throw the roe away here’. Yiayia looked at him bewildered. ‘What kind of country is this – look at us – we live like paupers and eat like kings’. So Yiayia and Papou salted and smoked the roe, then coated it with wax to preserve it, and it was strung on a line, like the washing, to dry out. This gourmet delicacy, Auvgotaracho was one luxury the family could dine on regularly. Today it sells for AUD $85 per kilo in Brisbane.

Many of their most loved foods, even simple things such as Greek coffee, were not available in Australia at that time. They grew their own Greek vegetables, horta, aubergines, okra etc. They made their own filo pastry. I can remember Yiayia and Papou standing at opposite ends of a long table and working the dough back and forth, stretching and pulling the doughy lump, waving it up and down, gently expanding it until the sheets were transparent and paper thin, the size of a bed sheet. When families visited each other, they would exchange vegetables, sweets, and little jars of yoghurt which they used as the starter for making their homemade yoghurt. Commercial yoghurt was unknown here until the 1960’s but back then, the Greek families were regularly making up their own jugs of yoghurt.

As ‘New Australians’, they were also a target on Saturday nights for the local drunks. At that time, Australia had restricted trading hours for the sale of beer and liquor. Hotel bars, which were restricted to men only, closed at 6pm. The aim of this law was to stop men getting drunk. The actual result was that, as the six o’clock deadline approached, there was a stampede at the bar as the men tried to drink as much as possible before the pubs (hotel public bars) closed. Thus, drunken men would be on the streets soon after six, looking for trouble. One form of this was to vandalise the shops of the local New Australians on a Saturday night. Tony says this didn’t seem to worry his parents unduly. After all the dangers they had lived through, a couple of inebriated men seemed relatively harmless. He says they just took things in their stride, routinely removing all breakables from the shop on Saturday afternoon then putting them back later in the evening. The local police would watch the proceedings but not intervene. So Papou, and all the Greeks, made a point of being very generous to the police. It was naïve not to do so, and with time and familiarity, protection and friendship were cultivated. Papou worked the shop seven days per week, and closed late, after the pubs, so that people could buy fish and chips for tea on their way home.

Papou’s English was adequate for serving customers in the shop. The government had no provisions for programmes to help migrants learn English in the 1920’s, and people had to pick up the language by trial and error. A basic, limited, repetitive vocabulary of nouns and verbs sufficed for meeting the customers’ needs and exchanging a few polite pleasantries. Dad thinks that his parents would have had an English vocabulary of no more than 100 words. Stock phrases such as –‘Hello, How are you? What would you like today? That one? How much? Very well thank-you. Nice day, Please & Thank you ‘etc. were enough to get meet their needs. However, anything out of the usual was a problem. One day the family’s horse escaped from the back yard and Papou ran to find a policeman. It was only when he was standing before the policeman that he realized he did not know the English word for ‘horse’. Despite his best efforts, without that key noun, he simply could not make himself understood. There were no Greek/English dictionaries available at the time, so he had to turn around and come home empty handed and frustrated.

It was not easy being different from the local population. When they went out, the family generally remained silent or spoke to each other in whispers. If people heard them speak Greek amongst themselves, they were told, “Speak English! You’re in Australia now”. And no one would dare read a Greek newspaper in public.

The members of the Greek community were supportive of each other against outsiders, but rivalries and jealousies occurred within. Dad remembers Yiayia being upset about their poor circumstances. Someone had made a comment about the way they were living and embarrassed her. “We can’t help it if we’re poor now,” she said. ”We had our nice house and business back Mikracea, just like them. It’s not our fault we lost everything. We’re doing our best.” To lose everything and start again, knowing they would never make up their losses was always going to be a bitter and hard thing for all the families.

Dad has many humorous vignettes, memories of curious incidents and experiences that stand out from those early days. Like video clips, they take us back to his childhood and provide glimpses of the family’s life. The family and their relatives were always trying to make life better for themselves in small ways. Yiayia’s brother and Papou watched the plump pigeons strutting around the back yard of the shop and dreamed of eating pigeon stifatho. One scheme they tried was to feed the birds wheat grains soaked in alcohol. The birds did wobble around on their legs a bit but were still able to make a getaway.

Their beloved ouzo was another thing they missed. All the Greek homes made their own stills for the purpose of distilling the alcohol, to which they added aniseed to make their ouzo. Owning a still and making alcohol was prohibited, and thus was done in secret. Someone informed on them, however, and told the police. Early one morning as the family awoke, there was a knock at the door. When Papou opened it, a dozen police rushed in and started looking for the still and bottles of ouzo. Dad and his brother were quickly dispatched to warn the other families nearby, but there were police cars waiting outside every Greek house, waiting for the occupants to rise and switch on the lights. The Greeks were nothing if not quick witted. In one family, the mother locked herself in the toilet, making one excuse after another, until she had flushed all their ouzo away. Another family put their grandmother to bed, surrounded her with bottles of ouzo, threw the covers over and sat around her praying, because, as they told the police, ‘our mother is dying”. Suspicions focused on a couple of disgruntled outsiders, but the community never did find out for certain, who the informant was.

Money was very tight. There was no money for luxuries and certainly not for toys for the children. Dad and Jack were enterprising lads, always looking for ways to earn some pocket money. It was the Brisbane custom for shopkeepers to wrap the cooked fish and chips in a sheet of clean white paper, then envelope this in a sheet of newspaper to keep it warm while the customer carried it home. So Papou and the boys collected clean, old newspapers for wrapping. Dad and Jack helped collect the old news sheets, but put some aside for their own use. The boys assembled the old sheets into a pseudo-newspaper. They then went to the tram stops and sold their ‘newspapers’ for a penny. People waiting at the stop for a tram were puzzled because the boys always refused to sell a paper to them. They sold only to commuters who were sitting on the tram, and only as the tram moved off. By the time their victims had opened the paper and realized it was made of the previous days’ sheets, it was too late. For this reason, the boys had two rules – they would not sell to people who were waiting at tram stops and they moved to a different stop each day to avoid meeting any old customers.

During their stay in George Street Dad remembers seeing the then Duke and Duchess of York. They visited Brisbane in 1926 and he remembers the streets were crowded with thousands of people waving flags at the royal couple in their open carriage. The family of penniless immigrant refugees had a dress circle position from the balcony of their first floor residence in George St. They waved and cheered enthusiastically, along with all the other true blue Aussies.

The family left the premises in George St with only one month’s notice as the landlady had sold the building. They moved to Mollison St at West End, a suburb close to the city which housed many Greek families, both relatives and friends. Here, Dad’s youngest sister, and last child to the family, Claire was borne. The family then made one more move to Thomas St, whilst Papou built a fine traditional Queensland home, in Vulture St., where they finally settled.

In those days, Dad recalls, a doctor was only ever called as an absolute last resort if someone was ill. No one ever went to hospital. Modern medicine was still thirty years away. The treatments for illnesses and accidents were the home remedies that had been passed on through families for generations. If anybody did visit a doctor, it was taken to mean that things were pretty bad for the patient. “What? They called the doctor? Oh no”, was a typical reaction. One day Dad was playing marbles in the street at the back of their house. A horse and cart suddenly came around the corner and ran over him. The driver tried to stop the horse, but it continued to trample him underfoot and it was several minutes before Dad was rescued. Papou carried him into the house, bleeding and covered in deep gashes and scratches from head to foot. Yiayia gently prodded him all over to establish that no bones were broken. Then she looked at his open wounds covered in dirt. She wiped him clean, and made a poultice (a warm, moist dressing) of mashed onions, which she pasted thickly over his legs, arms and trunk. She tore old sheets into strips and wound the strips over the poultice, around his body and each limb, so that he was wrapped up like an Egyptian mummy. She kept him like this for two days. He remembers the strong pungent smell of the onions and their fumes stinging his eyes. However, he recovered without any infection. I think this is quite remarkable considering that dirt, manure and other infectious material would have been on the horse’s hooves. Antibiotics such as penicillin did not exist at the time. It was his mother’s home remedy and his own immune system that pulled him through. In those years even a simple little scratch could become infected, develop into septicaemia and cause death. And yet, remarkably, Dad’s whole family survived all the childhood illnesses and accidents.

Whenever the family caught a cold or flu, Yiayia would apply her ‘koupes’. She took a small twist of tissue paper and dipped it in a little methylated spirits. She lit this, placed it on the patient’s bare back, then immediately covered it with a heavy, wide mouthed, glass tumbler. As the tissue paper burned, it used up the oxygen in the tumbler, creating a vacuum. The vacuum drew the skin under the tumbler upwards, in an arc. The resulting stretch on the skin caused the pores to open very widely. This opening of the skin pores was thought to draw out the illness. In a standard treatment session, several tumblers were placed on the back at the one time. As a young child, somehow, Dad had never seen his mother give this treatment. Thus, when he took ill with a cold and she applied her koupes, he was so horrified at what she was doing, that he tore off down the main street of Brisbane bare chested and bare footed, with six tumblers attached to his back and the family in pursuit. Yiayia also had a stronger version of this treatment which she reserved for more severe colds and flu’s. This was called ‘koftes koupes’. She used the same technique, but she made small incisions in the skin before applying the lighted tissue and tumblers. This method caused excess bleeding in the vacuum seal under the tumbler, and was thought to enhance the drawing out of the illness even more. Yiayia was a firm believer in her home remedies. As a teenager, I can still recall her coming to our home to apply her “koupes” to my father, then in his forties, whenever he succumbed to the ‘flu. He clearly did not relish the treatment but had no choice but to dutifully lie down and take what was coming. He has, it must be said, enjoyed robust health all his life, so, who knows…..

Dad went to St Mary’s Catholic primary school, only days after they arrived in Brisbane. He was about five years old. He could speak no English and there were no English language classes for the immigrant children. He was just put into a classroom and expected to pick up the language and keep up with the class. I asked him if he remembered how he learned English. He could not remember a process as such, but he says he noticed that what people were saying, started to gradually become clearer to him, day by day. I think that the highly structured classroom environment and routines, plus the heavy emphasis on rote learning, which was the norm in schools, then, would have assisted him. In the playground, he would have observed many contextual cues from the other children, whilst he watched the play games such as Tag, Marbles, Cricket or Football etc. He would have carefully watched their body language, facial expressions and tone of voice to guide him in interpreting what was going on.

Dad felt he was making good progress with his English, when a particular song became popular on the radio. Everybody was singing it but Dad could not fathom its meaning. This really confused and panicked him. He was worried that his strategies for learning English were faulty and he wondered what else he was getting wrong. This really shook his confidence and self-reliance at the time. Many years later as an adult, he heard the song again and realized it was simply a pretty, “nonsense” song that had caught people’s imaginations. The words were ‘Here we go looby loo, here we go looby lie, here we go looby loo, all on a Saturday night’. No wonder it confused him. So although he does not remember the actual process of acquiring English, his brain was obviously working very hard to pick it up phonetically and contextually.

During the World War 2, Papou made a lot of money through selling coffee. Coffee was unknown to Australians at that time. Tea, in the British tradition, was the staple beverage. After arriving in Australia, Papou asked his brothers in America to send him a coffee grinder and to supply him with coffee beans. He built up an income on the side, roasting and grinding beans to make Greek coffee to sell to the Greeks in Brisbane and country areas. When the American army came to Brisbane in the Second World War, they could not believe that there was no coffee for their soldiers. When they heard about Papou and his coffee grinder, the Yanks, as the Aussies referred to the Americans, began arriving at Papou’s house every day, the army trucks laden with coffee beans. His coffee grinder worked day and night.

It must be said that those early refugees from Asia Minor were a hard working, resilient, adaptable, self-reliant group of people. They had no fallback position, no government assistance, and no pension. Remember that two generations went through this simultaneously – the parents and their children, and the experience affected them in different ways. History records the refugee experiences from the adults’ perspective, but their children started life as refugees as well, working alongside their parents to put food on the table and keep a roof over their heads. The formative years of the children were sandwiched between two world wars, against a background of escape, migration and the Great Depression. Somehow both generations seemed to emerge from their experiences intact, although their suffering left its mark and cast a long shadow. From my family’s experience and that of others I have spoken to, this first generation parents did not want to talk about what had befallen them for many years, if at all. Many of their children have said that even when asked repeatedly over the years, their parents would find a way to avoid giving a direct answer, and change the subject.

Australia has been good to our family and to all who have come to her shores seeking a new life. At the time of my father’s arrival, Australia was a young, undeveloped, insular society. They did encounter discrimination, but they also made good Aussie friends, and their civil rights were protected by law. They worked hard, and did their level best to fit in. As individuals and as a community, they helped their own people, and contributed to the Australian community, through cultural, charitable and civic activities. The Greek Orthodox Church and Greek schools have been active in teaching their faith, language, history and culture from the 1920’s. The immigrants had to make compromises, but they did not have to forfeit one single thing of value, to live here. Not their language, not their customs, and not their faith. We will always be thankful that our families had the chance to start afresh in such a tolerant, peaceful and fair society. Tony and Jack, with many other young Greek men, served in the Australian Army in World War Two. They repaid their new homeland by fighting in New Guinea and the South Pacific doing their duty as “true blue Australians”.

In 2004, a function was organised to celebrate the culture, history and music of Asia Minor. All the remaining survivors of the Catastrophe in our Greek Community were honoured in a special ceremony. Each was presented with a gold medallion and the survivors were asked to cut a commemorative cake. My Aunty Angie found herself in the middle of the group, with the cake knife in her hand. Beaming widely, she pulled her brother Tony to her side. She clung tightly to his arm as they cut the cake and had their photos taken. A few months later, she had a minor heart attack and we visited her in hospital. “That was the best night of my life,” she told me. “Better than my wedding day”. “Oh, Aunty Angie -”, I said, “ surely not better than you’re wedding day”. “ Oh yes it was” she said, smiling broadly, “in my whole life, nobody has ever made a fuss of me like that. It was lovely being the center of attention, just for a little bit”. A few months later, she quietly passed away in her sleep. I think of all those survivors that evening: my aunt, Angela, a little girl who lost her mother at three and her country at eight; my father Tony, a little boy transplanted here at the age of five and thrown headlong into a new culture; and every one of those amazing people with their own miraculous story. After all they had survived, I am very glad, that for a few minutes, on one evening in Brisbane, we recognised and applauded these inspirational lives.

POSTSCRIPT

Angela married Chris Mouzouris and had four children – Jim, Rene, Marcia and Con

Alexandra married Peter Crethary and had two children – John and Anthea.

Tony married Mary Girdis and had three daughters – Mary-Ann, Lorraine and Eleen.

Jack married Urania Nou and had three sons – Con, Glen and Paul

TONY’S LIFE OF CONTRIBUTION AND ACHIEVEMENT

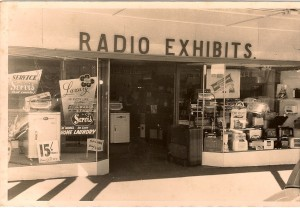

During World War 2, Tony served with both the 64th Battalion of the Australian Infantry and the 109 Engineers. He saw action in Port Moresby, Lae, New Britain and Bougainville. His rank was that of Staff Sergeant. When the war ended in 1945, Tony returned home. In 1946, he married Mary Girdis. He worked as an electrical appliance retailer and repairer in his own business in Wooloongabba. He and Mary had three daughters, each of whom was given a tertiary education. Mary-Ann became a Physiotherapist, Lorraine, an Early Childhood Education Teacher, and Eleen, a High School Teacher. Tony went back to night school while his family was young. He completed the last two years of Secondary School then obtained his Batchelor of Science and Batchelor of Education degrees. He changed careers and became a Lecturer at South Brisbane TAFE in 1971. He was promoted to Education Officer (Head Office) in 1982, and further promoted to Officer in Charge, Electronics and Communications, until his retirement at the age of 65. He still studies part time and helps his daughter and son in law with their business. He is still active in AHEPA and he is a past State and National President of that organization. He has been active in the RSL since 1950. He was on the building committees of both The Greek Orthodox Church of St George, South Brisbane, and the Greek Orthodox Church of the Dormition of the Theotokos, Mt Gravatt.

As a first generation refugee who grew up in Brisbane, he has made significant contributions to both the Australian and Greek communities.

REFERENCES

Miller, Tony. Personal (audio and video) taped interviews. January 2004. His memories of the Miller family’s early life in Brisbane.

Mouzouris, Angela (nee Miller). Personal (audio) taped interview. January 2004. Her memories of the Miller family experiences before and immediately after the Catastrophe. My thanks to the Mouzouris family for their kind permission to use their mother’s memories in this story.

de Vries, Susanna. 2001, Blue Ribbons Bitter Bread, Hale & Iremonger, Alexandria, NSW, pp153-178. This book provides excellent background information relating to the conditions endured by the refugees of Asia Minor.

Doidge, Norman. 2007, The Brain That Changes Itself, Scribe, Melbourne, pp 298-299. This section of the book examines how the brain adjusts to the migration experience.

Milton, Giles, 2008, Paradise Lost, Sceptre, Great Britain. This book provides excellent historical information that surrounded the events of 1922.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank my Aunt Angela, who shared her memories and those of the family’s history so unstintingly, and to her children, who kindly gave me permission to present them in this story.

I would like to thank my husband, Dr Foti (Frank) Inglis, the amateur historian of our family, who virtually wrote the Foreword for me.

Angela Mouzouris & great grandchild

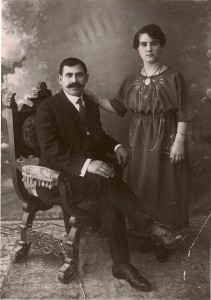

Constantine and Marianthe Malliaroudakis

Miller passport photo en route Australia

Miller family home

Tony army photo

Tony with the army in New Guinea

Tony and Japanese POWs.

Tony and Jack in Youth Club tennis team

Tony & Mary Miller (Girdis)

Tony’s shop at Woolloongabba

Tony, Mary Miller, Chris, angela Mouzouris, Peter, Alexandra Crethary, Peter, Claire Notas, Jack, Ourania Miller

Angela and Tony at Asia Minor dinner